The map creates the territory

Paper towns and how maps have power.

Hey friends, welcome back.

Last week, we talked about how the map is not the territory. We ended by recognizing that “we must be ready and willing to abandon the map when it begins to fail us and to consider what different maps might serve us better.”

We talked about situations where maps were wrong. Sometimes, intentionally wrong. But what happens when the map maker makes an intentional error, and then that error… becomes real?

Consider Agloe, New York. If you have a few minutes, watch this video of John Green explaining (the whole video is great, but the first few minutes are the relevant bit):

If you don’t have time for a watch, a quick summary from Wikipedia:

In the 1930s, General Drafting founder Otto G. Lindberg and an assistant, Ernest Alpers, assigned an anagram of their initials to a dirt-road intersection in the Catskill Mountains:… The town was designed as a "copyright trap" to enable the publishers to detect others copying their maps.

In the 1950s, a general store was built at the intersection on the map, and was given the name Agloe General Store because the name was on the Esso maps. Later, Agloe appeared on a Rand McNally map after the mapmaker got the name of the "hamlet" from the Delaware County administration. When Esso threatened to sue Rand McNally for the assumed copyright infringement which the "trap" had revealed, the latter pointed out that the place had now become real and therefore no infringement could be established.1

So the town, created as a cartographer copyright trap, came into existence. Today, the “town” no longer exists: the general store that popped up has since closed, but an arbitrary choice by a map-maker did change something about the “real” world.

Let’s consider another example: the 35th parallel:

…the king of England sent surveyors to draw a boundary between the two Carolinas. His instructions in 1735 were explicit: Start 30 miles south of the mouth of the Cape Fear River and have surveyors head northwest until they reached 35 degrees latitude. Then the border would head west across the country to the Pacific Ocean.2

Of course, at that time, no one had any conception of how far the Pacific Ocean was. But the 35th parallel became the technical boundary.

But the surveyors didn't follow the instructions exactly, and future instructions led to the state line's twists and turns around Charlotte and in the mountains.3

If you’re not familiar with the geography of Carolinas (or if you are but the exact position of the 35th parallel isn’t burned into your mind), here’s a map that can help you envision what it might have looked like if the original instructions were followed:

You can see the 35° line running through the middle there. To make it a bit more clear, here’s a map of just South Carolina today:

The 35° line can clearly be seen cutting off the tops of Pickens, Greenville, Spartanburg, and many other county lines. For reference for my readers in Greenville County, that would put the line running through Lake Robinson near Greer.

North and South Carolina have come to terms with the fact that the line doesn’t exactly follow the 35th parallel, but there were still a number of places the territory didn’t exactly match even the modified map that the surveyors laid out. As it turns out, those errors in recording the line centuries ago have real-world consequences. Take a look at what the difference in a fraction of a degree means today for a resident of South Carolina (and now North Carolina?) today:

Relatively small errors by surveyors using stakes, hatchets and mental arithmetic 240 years ago could mean the end of Victor Boulware's tiny convenience store.

For decades, officials thought the land where the store sits was in South Carolina, because maps said the boundary with North Carolina drawn back in the 1700s was just to the north.

But modern-day surveyors, using computers and GPS systems, redrew the border to narrow it down to the centimeter. Their results put the new line about 150 feet south of the old one and placed Boulware's Lake Wylie Minimarket in North Carolina, where the gas prices are 30 cents higher and the fireworks that boost his bottom line are illegal…

For most of the 14 million people in both Carolinas who live far from the state line, the new survey is an interesting tale that might bring up a joke or two. Will the people who suddenly find themselves in North Carolina have to start liking basketball more than football or renounce mustard-based barbecue sauce in favor of the styles preferred to the north?

But for the owners of 93 properties who suddenly find themselves in another state, it's a bureaucratic nightmare. The state line determines so much in their lives — what schools they go to, what area code their phone number starts with even who provides them gas and electricity. Small utility cooperatives in South Carolina are banned from extending services across the state line. Most of the properties in question are near Charlotte, N.C.4

North Carolina and South Carolina have largely solved their differences around the state line, but as it turns out, the 35th parallel has also created trauma further west. See, the supposed line between North and South Carolina, if it has been drawn in the right place, should have become the boundary between Tennessee and the other southern states. Of course, this didn’t exactly happen:

Georgia lawmakers say the state’s northern border with Tennessee and North Carolina is in the wrong place, and they want to explore moving it. It’s a long-running dispute that’s come up a number of times over the years in the state Legislature, and it’s all about access to water.

Georgia has fought with other states — Florida and Alabama — for decades over the rivers those states share…

Meanwhile, there’s another big river just outside of Georgia’s borders: The Tennessee River. It’s just over the state line, in Tennessee. In fact, some creeks that start in Georgia flow north and feed into the Tennessee River.

Some lawmakers here say Georgia should be able to use the water in Tennessee because if the state line were in the right place, some of that river would be in Georgia.5

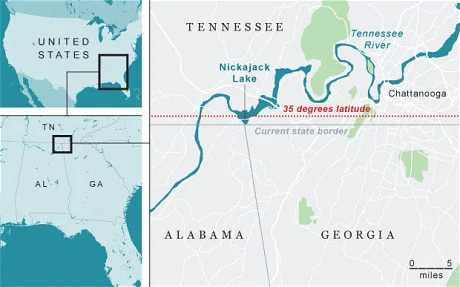

Here’s a map of the difference:

In case it’s hard to tell, the “water war” boils down to this small difference:

So if the border were where it should be, a portion of the Tennessee River would be in Georgia, giving Georgia a right to use its water to quench the thirst of the Atlanta Metro Area.

So, what do these two situations have in common? For both Agloe and the state line issues, something was put on a map, and thereafter the map shaped the land. For Agloe, a place that was made up came into existence. In the state line situations, the line was put on a map but was measured incorrectly at first. Today, with better technology, we have changed (and may further change with the Tennessee/Georgia dispute) the situation on the ground to be faithful to the map.

Maps have power, and as we talked about last week, the map is not the territory.

Maps change the territory by framing how we think about the lay of the land.

Most of us don’t have the responsibility of making maps of towns and state lines, but many of us make decisions that inform others how to conceive the world.

It may be an active choice: we’ve all seen or perhaps used data visualizations that make our data look a bit better than it might otherwise.

It may be a moment when we’re caught up in an argument: Godwin's law holds that in internet-based conversations, “the longer the discussion, the more likely a Nazi comparison becomes, and with long enough discussions, it is a certainty.6

We may not be aware that we’ve given someone a bad picture of the world: Humans are metaphor machines, but unfortunately, we frequently misapply or take them too far.

Regardless, these decisions (either active or passive) have consequences and change the lay of the land for ourselves and others. Let’s be mindful of our map-making choices and consider how we could be charting new land in a faithful way rather than distorting the map.

With that, see you next week.

Stray Thoughts and Further Reading

If this story feels somewhat familiar, it might be because it was used by Green as a narrative element in his 2008 book Paper Towns. That book was then adapted into the 2015 movie by the same name. I’m not afraid to admit it: I do enjoy the Young Adult Fiction Novels of John Green. You may know him most famously for his book The Fault in Our Stars. I’ve been an avid listener to the podcast he does with his brother Hank called Dear Hank and John since its beginning. He and his brother are also known for their Youtube Channel vlogbrothers.

The article The Mississippi River does not care for your man-made borders contains a lot of other great examples of this type of map-territory dispute.

I love the map comparisons of earlier choices having a huge impact on others down the line. For years I used the phrase, “Play the tape”….referencing tapes for a tape recorder or a video in order to realize how actions and decisions in our stories would play out in the future. Your map examples are much better because they are timeless, but tape recorders and VCRs were not. powerful. Thanks, Alex.