Hey team, welcome back!

So, as you can probably, tell, we’ve been on a map kick lately. Maps are a helpful metaphor for our knowledge and give us a way to talk and think about it, so I have an announcement: We’re renaming “Context&Context” to “Fun with Maps with Alex!”

Just kidding, but also maybe one day?

In all seriousness, thanks for continuing to read. I do hear from some of you all ever so often, so thanks for that as well. I do love hearing your feedback!

If you enjoy reading, consider sharing with a friend.

To start today, if you have time, please watch the first five minutes of this video:

For the TL;DR version:

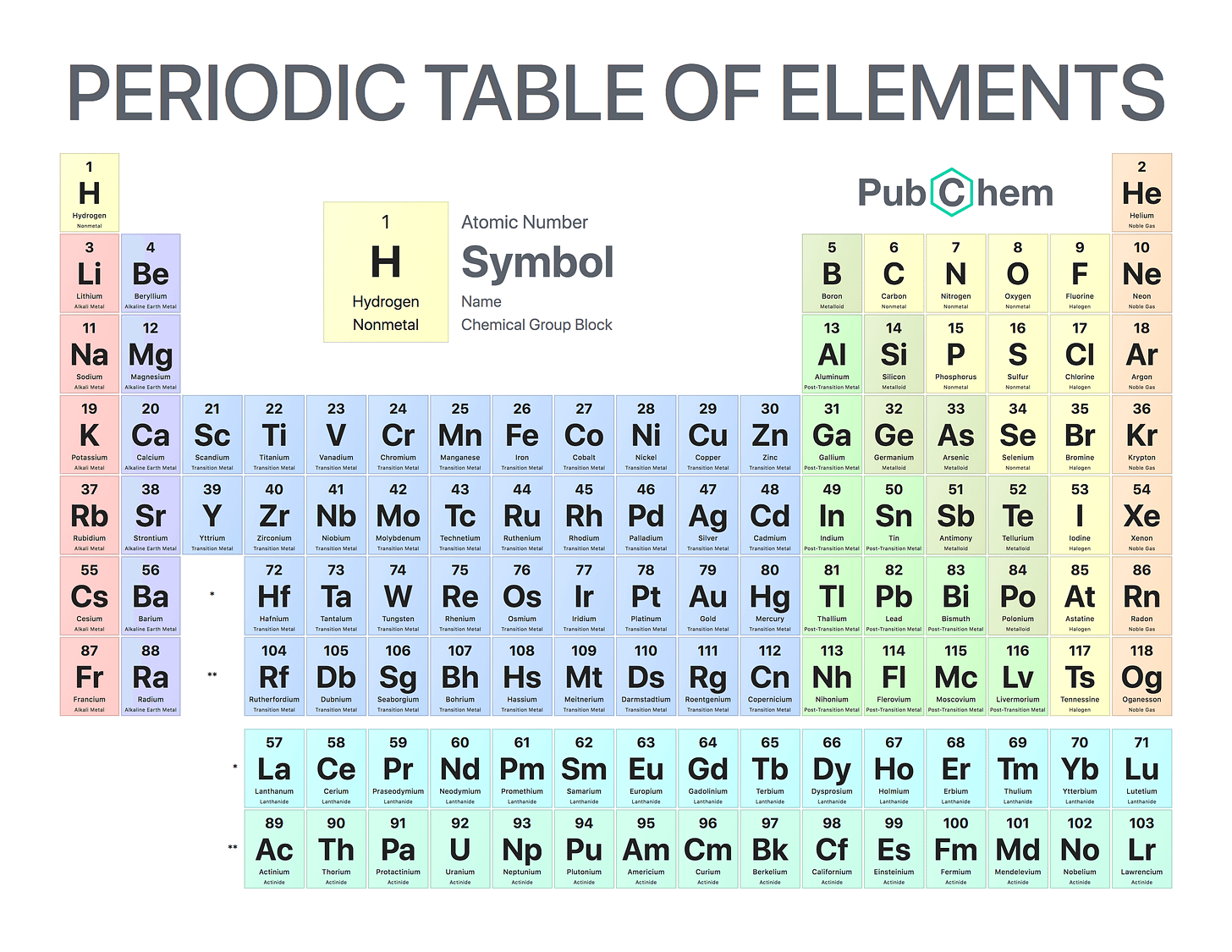

Dmitri Mendeleev published a periodic table of the chemical elements in 1869 based on properties that appeared with some regularity as he laid out the elements from lightest to heaviest. When Mendeleev proposed his periodic table, he noted gaps in the table and predicted that then-unknown elements existed with properties appropriate to fill those gaps…

The four predicted elements lighter than the rare-earth elements, eka-boron (Eb, under boron, B, 5), eka-aluminium (Ea or El,[2] under Al, 13), eka-manganese (Em, under Mn, 25), and eka-silicon (Es, under Si, 14), proved to be good predictors of the properties of scandium (Sc, 21), gallium (Ga, 31), technetium (Tc, 43), and germanium (Ge, 32) respectively, each of which fill the spot in the periodic table assigned by Mendeleev. [Emphasis mine]1

So by figuring out a more helpful way to “map” the elements, Mendeleev figured out the pattern in their properties. Using that pattern, he was able to predict the properties of the yet undiscovered elements sight unseen. In Mendeleev’s case, his table looked like this:

Over the years, it was revised to get to its current form:

So by figuring out the pattern and creating a new table of elements based on that pattern, Mendeleev uncovered a constructive way of laying out the elements, which allowed him to predict their properties.

As it turns out, however, there’s more than one way to layout the table.

Throwing back a few weeks, you may remember a phrase George Box is often quoted as saying:

All models are wrong but some are useful.

So far over the past few weeks, we’ve focused a lot on how maps fail us: where they paint bad pictures of the world. But by focusing on a few really wrong maps, we risk implying that some maps might be “more right” than others. So let’s pause to take it in: all maps are wrong.

But what does it mean to be wrong?

Much like climbing to the peak of the next mountain reveals more territory we couldn’t see earlier, it is more helpful to think of maps not as good or bad but as more or less helpful. What would different maps be helpful for? Towards accomplishing different ends.

In this sense, maps are metaphors. As we’ve talked about before, all metaphors break down, but that’s not to say the map is itself wrong. It just has a limited-use case.

Our minds are marvelous creations, but they like to take shortcuts: we don’t contain the contexts of metaphors very well. Our brains “jump to conclusions… if the conclusions are likely to be correct and the cost of an occasional mistake acceptable, and if the jump saves much time and effort.”2

Once we understand the metaphorical nature of maps, we can remember to treat any particular map just as a way to relate the information about the thing being mapped.

There is no “right map” and “wrong map” if the source material is factually correct; there are just different maps for different ends.

Take a look at the table below:

Does that look like any periodic table you’ve ever seen? I had not, but it is a different way to lay the elements out that shows other meaningful relationships. If you visit the webpage linked in the caption, there are many different alternative versions of the periodic table. Each services a different end, helping us see the relationships between elements in a more clear way.

Think back to our discussion in The map is not the territory. The Mercator projection isn’t “wrong” because it distorts the truth; all maps distort the truth. It’s impossible to make a map that doesn’t trade off a little bit of the truth for the convenience of understanding the reader; that’s the nature of metaphors. Is it the most useful map to show the spatial relationships between parts of the world? Probably not. It’s great for helping ships sail across oceans, though!

So why all this talk of tables and maps and metaphors? It’s tempting to imagine things like the “best or worst” and “right and wrong” ways to represent information. Or different theories as better and worse ways of understanding reality.

But by and large, maps are more like metaphors. They relay information to us in a way that helps us understand it in different ways. That’s not to say maps are “value-neutural.” There are clearly some “maps” that make moral assumptions that we need to consider when using. And just like different media have different biases that guide our thinking, the map we use guides our thinking about the territory being represented. Some metaphors are more helpful in some contexts than others, but that doesn’t mean the metaphor is “right or wrong” in the strict sense.

This is another of those pesky spots where we arrive at a tension:

On one end, some maps are more helpful than others and are better fits for different situations.

On the other, no map is completely right and therefore all maps are a little wrong.

The point in all of this? We should be mindful of the maps that we use. Instead of picking up what we’ve always done, perhaps there is a more helpful option for our current situation. Or perhaps there’s a way of thinking we’ve completely shut out because it’s completely “wrong,” but by doing that we’ve close off an entire approach to knowledge. Let’s think better about our thinking, and see what different maps can teach us about our territory.

With that, thanks for reading. Catch up with you again soon!

Notes and Further Reading

A long time ago, we talked about metaphors. Check it out here:

This article had some interesting points about maps as metaphors, but a lot of the territory (see what I did there?) covered points back to our article from a few weeks ago.